“Hero” is a term usually used to describe someone who has noble qualities, can conquer outstanding feats, and is the embodiment of courage and valor. The hero(ine) is the person who saves the day against all odds, sometimes without rest and without thanks, and battles on to right the world’s wrongs. They are superhuman – superheroes – and we look up to them and admire them. In games, we are asked to identify with them, and we try really hard.

Except we can’t. We can’t look at Superman in all his super strong, bulletproof glory and say to ourselves, “Yes, self. I am just like that.” We want heroes who are weak. We want heroes who have baggage. And we want heroes who fail, at least a little bit.

Now, this isn’t to say that we don’t like perfect heroes, or that it’s not fun to play as a super-powered being, because a lot of games play into this sort of power fantasy. But, when we’re talking about heroes and avatars that we can relate to, the more human a character is, the more we will naturally find ways to relate. These characteristics can bypass things like physical appearance, and even gender, as long as core traits or even life experiences are relatable.

In fact, within the hero’s journey, which is something we talked about a long time ago in two parts, the hero is actually expected to fail a few times on their quest before becoming the hero. For a brief recap, the hero’s journey is the path that most (if not all) heroes in mythology have followed to transition from average human to heroic powerhouse.

Making the Perfectly Imperfect Character

Before we talk games, we need to talk a bit about relatability. While there are many character aspects that go into making a character relatable, and many psychological reasons for this, when it comes to having a flawed hero, two points are of paramount importance: the hero must have an ordinary flaw, and the flaw must be forgivable.

By ordinary flaw, I mean one we can relate to. For an extreme example, while we might relate to Thor if all of a sudden his immense strength decreased, we’d quickly lose all empathetic feelings if we found out that his hammer could only weigh as much as 200 billion elephants now, instead of 300 billion elephants.

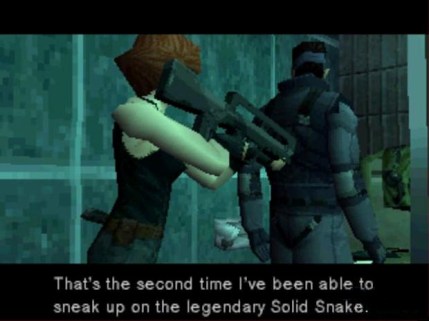

These two points are important to keep in mind, because the ordinary flaw humanizes the character, but we as the viewer/player must also think that the character can be redeemed. For an extreme example, Solid Snake is a tough, no-nonsense super spy who can kill you with his bare hands (something unrelatable to many of us), but he has some trust and intimacy issues (which, even if we can’t personally relate, we can empathize). But – and this is critical – we can understand why Snake has his issues, and we can forgive him for keeping people at an arm’s length.

On a smaller scale, when we see him fail in little ways, it drives home that he’s still a human who can make mistakes, like in the Metal Gear: Solid example here:

When he makes mistakes, when he doesn’t see the twist at the end coming, and when things don’t work out the way he wanted, he is actually successful in burrowing into our hearts a little more.

The Power of Pathos

Humans are flawed, and so it’s easy to see why we might identify with a character who shows flaws, especially if they are ordinary. But in a virtual world where we can be anything, why would we choose to follow the exploits of a character who makes mistakes, and experiences heartache?

As we’ve discussed elsewhere on this blog, empathy is a feeling that drives us to relate to other people and experience what they are experiencing. Humans are, in fact, emotional beings. So, when we are exposed to a character with an emotional backstory, we get wrapped up in the pathos, because it gives us an emotional “fix,” if you want to think of it in those terms. (For a quick-and-dirty guide to what pathos is, you can find one here)

But this again begs the question of why. Why do we want to experience negative emotions, if we have the option? The answer is surprisingly simple: by being given the opportunity to feel these emotions behind the safety of a screen (or behind the pages of a book), we are given a chance to experience these emotions within a safe context. If a person dies in real life, you can’t pause life to process what just happened, and you can’t distance yourself and look at the grief with a critical eye.

You can do that with a game. You have control over how you experience those emotions. You can pause the game; you can even turn it off and come back to it later without consequence. In real life, there’s no actual “pausing to come back later.” It’s happening, and you can’t just “turn it off” until you’re ready to deal with it.

Games let us explore these scary and “unsafe” emotions from a safe distance, and let us experience and practice what it would be like in those situation, were they to be real.

The Big “So What?”

Relatability is immensely important in creating character depth and for fostering interest in the character, because relating to another person is more powerful than looking up to someone perceived as “perfect.” We want to build connections with other humans and, as we’ve talked about before, we want to see that we – with our flaws – can move beyond what we are and become the person we want to be.

When we find and relate to a character who is like us, we are also free to experience their emotional experiences from a safe distance. We can feel the pang of death, rejection, or failure without actually having lost anything; we can feel rage, anger, and hatred without risk of harming something real; and we can feel the powerful rush of pride when we accomplish something difficult, spurring us (hopefully) to seek that feeling in the physical world.

All Those Who Wander…

One such hero is Wander from Shadow of the Colossus. Although he’s a pretty quiet character, we are immediately drawn in to his story as he tries to save the life of the woman he loves by going on and epic quest to kill the titular colosi. His flaw is that he is in love… When the twist at the end happens, I’m not sure any of us sat there thinking, “Good, you deserved that,” so his flaw – which drove his actions – was forgivable. We were probably rooting for him, and maybe a little depressed when the heroic quest didn’t work out in the end (at least for him). This is a game that is critically acclaimed for not only its art and story, but its characters. There’s only one character, and he doesn’t say much, so the only thing we can relate to are his actions (which aren’t flawed) and his motivations (which are).

What do you think? What beautifully flawed heroes do you like, or do you prefer your heroes to be perfect in every way? Let me know in the comments!

Until next time, thanks for stopping by, and I’ll see you soon!

~Athena

What’s next? You can like and subscribe if you like what you’ve seen!

You can also:

– Support us on Patreon, become a revered Aegis of AmbiGaming, and access extra content!

– Say hello on Facebook, Twitter, and even Google+!

– Check out our Let’s Plays if you’re really adventurous!

Very nice post! 😊 if you havn’t played it, I suggest firewatch – it is all about characters who are relatable and flawed.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for your comment! I’ve seen a few Let’s Plays of (the beginning of) Firewatch, and I agree! It’s on my list of my ever-growing list of games-to-play! Thanks for the recommendation! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

☺️… Agreed, that list never seems to get any shorter…

LikeLiked by 1 person

The Greek tragedy plays so much on this, the flawed hero and the catharsis the audience experiences at the end. I think it all comes down to accessibility. We want our heroes to be accessible in some way. Superman is great as a paragon, moral compass, or someone to look up to, but you can’t really empathize with an all powerful being, and even his kryptonite flaw doesn’t really lend itself to the human experience, but everyone can understand the example you give with Snake. If perfect characters like Superman save the day, that’s just par for the course, but if characters who while possibly super powered, but with relatable flaws make it, then it gives us hope that our little, flawed selves can to.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Accessibility is absolutely the root cause of wanting imperfect heroes. Have you ever read the book The Hero With a Thousand Faces? It outlines the history of the hero’s journey in human narratives (if you haven’t, maybe skim it… it’s a little slow sometimes). The path of Greek tragedy fits, with the whole story being based on the hero being brought low before the story begins in earnest.

Of course 🙂 We want to be like our heroes, so if they can overcome their human flaws and achieve greatness, so can we!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh my goodness yes. That is one of my favorite books of all time! I’ve read it twice and love Joseph Campbell. The Hero’s Path quote is one of my favorite quotes of all time, and I’m constantly referencing Hero. I think it’s the answer to one of my Questions of the Week, and I’ve made a few macros featuring it. The part in FFIV where Cecil becomes a paladin always brings parts of it to mind. I have The Power of Myth next on my TBR list. Campbell was a true mast of mythology.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think the forgivability aspect of it is a big one that a lot of writers unintentionally get wrong. Consumers will tend to be a lot more critical of the personality flaws than they might for people in real life, but a less critical of the more singular event based ones than they would in reality, so you can’t quite base that off of reactions in real life, but at the same time, it’s such a heavily subjective thing, that what might make a flaw forgivable to the creator may not come across to the viewer.

Add in that it’s really easy (and fun!) to find unintentional character flaws, and yeah. Flawed characters are absolutely necessary for a good believable narrative, but it can be a minefield to create them.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, it’s hard to write a good, believable character; I think sometimes people overthink their characters instead of just trying to describe a *person.* I had a writing professor once tell me that if I wanted to write a believable character, I needed to – basically – roleplay a little. What was the character’s background and motivations? As a writer, knowing those things will naturally lead the character to make mistakes sometimes, or have a personality flaw. This helps the character be forgivable – or at least understandable, which is another way of identifying with a character – because you’re right, being able to forgive/understand the character is a *huge* part of being relatable!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Been thinking about elements of this myself, but you were able to masterfully get them down in writing 🙂 kudos!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! Glad you liked it, and I’m always happy to help 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

As someone who regularly gets ambushed by armed women, I can certainly relate to Solid Snake.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That seems like it may or may not be a good problem to have…? haha

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is a very good post, and it gladdens an old geek’s heart to see that he is not the only one that relates pathos to gaming…I would say, you said we want weak heroes, right back at the start. I don’t think you meant weak. You use flawed the rest of the time and I think that is right.

Relatability is important, I have often bored friends with discussions of recent reboots which are really good because they are gritty, but by gritty, I mean more realistic (Battlestar Galactica springs to mind). I think there is another reason we want flawed heroes, particularly in games.

A game is a story, and a story is a journey. Forgivable flaws define a start point for the journey, and set the the hero on a path. A videogame is likely to be a quest narrative, a journey as it were. However, if the hero has a flaw that is relatable they have a personal/spiritual journey too that we the reader/viewer/player have an empathetic link to, meaning we join them on that journey and then on their physical journey. This results in greater immersion.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for your thoughtful comment, and good eye catching the word “weak.” I can understand where you are coming from, which is why I used the term “flawed” for the rest of the article, but I did use that word on purpose. It was meant to strongly contrast with the Superman image that I had used earlier. But you make a valid point that flaws can go beyond physical weakness.

And I will certainly agree that relating to characters makes for a more immersive experience! I know I’ve talked a lot about characters and avatars on this site, so I’m glad to see that you have similar ideas about storytelling and video game characters! 🙂

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Sharp Writing and commented:

This is a very good post I found on another blog. I would say, where the author references weak heroes right back at the start, I don’t think they meant weak. Flawed is appropriate though.

Relatability is important, I have often bored friends with discussions of recent reboots which are really good because they are gritty, but by gritty, I mean more realistic (Battlestar Galactica springs to mind). I think there is another reason we want flawed heroes, particularly in games.

A game is a story, and a story is a journey. Forgivable flaws define a start point for the journey, and set the the hero on a path. A videogame is likely to be a quest narrative, a journey as it were. However, if the hero has a flaw that is relatable they have a personal/spiritual journey too that we the reader/viewer/player have an empathetic link to, meaning we join them on that journey and then on their physical journey. This results in greater immersion. This works in written fiction too

LikeLiked by 1 person

The most obvious failed Hero is from one of my favourite books: the Illiad. It could be argued that Hector is the true hero of the book. His only concern is to save his people. This differs from the selfish actions of the Argives, Paris and even the Gods themselves. In the end, despite being a good and honourable man, Hector fails.

I love Sucker Punch. I would say that Baby Doll is the ultimate failed heroine. Not only does she fail to find a free and happy life, but she finds out she is not actually the true heroine of the story. (Perhaps Achilese realises the same thing in the Illiad).

Another is Rico from Starshiptroopers. Although he survives to the end movie, he loses the girl who loves him and failed to get the girl he loves. But it wasn’t intended to be like this. In the original ending that was produced, I believe Rico does get the girl (Carmen). But test audiences reacted badly as they thought it was disrespectful to Dizzy who died in his arms. The are many cut scenes with Rico and Carmen kissing that never made it into the movie.

You could now argue that the protagonists of the Star Wars OT are all failed heros. In Force Awakens the New Republic is destroyed and the Sith Empire is resurgent, effectively meaning that all their efforts in the OT were for nothing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for sharing your favorite flawed heroes! The comparison to Star Wars is certainly an interesting idea! I suppose a counterargument to that would be that they succeeded at the time, and the resurgence of the Empire wasn’t their “fault,” rather it was simply the cycle of good/evil continuing. But I’ll have to think on that a little more!

LikeLiked by 1 person