“Hero” is a term usually used to describe someone who has noble qualities, can conquer outstanding feats, and is the embodiment of courage and valor. The hero(ine) is the person who saves the day against all odds, sometimes without rest and without thanks, and battles on to right the world’s wrongs. They are superhuman – superheroes – and we look up to them and admire them. In games, we are asked to identify with them, and we try really hard.

Except we can’t. We can’t look at Superman in all his super strong, bulletproof glory and say to ourselves, “Yes, self. I am just like that.” We want heroes who are weak. We want heroes who have baggage. And we want heroes who fail, at least a little bit.

Now, this isn’t to say that we don’t like perfect heroes, or that it’s not fun to play as a super-powered being, because a lot of games play into this sort of power fantasy. But, when we’re talking about heroes and avatars that we can relate to, the more human a character is, the more we will naturally find ways to relate. These characteristics can bypass things like physical appearance, and even gender, as long as core traits or even life experiences are relatable.

In fact, within the hero’s journey, which is something we talked about a long time ago in two parts, the hero is actually expected to fail a few times on their quest before becoming the hero. For a brief recap, the hero’s journey is the path that most (if not all) heroes in mythology have followed to transition from average human to heroic powerhouse.

Making the Perfectly Imperfect Character

Before we talk games, we need to talk a bit about relatability. While there are many character aspects that go into making a character relatable, and many psychological reasons for this, when it comes to having a flawed hero, two points are of paramount importance: the hero must have an ordinary flaw, and the flaw must be forgivable.

By ordinary flaw, I mean one we can relate to. For an extreme example, while we might relate to Thor if all of a sudden his immense strength decreased, we’d quickly lose all empathetic feelings if we found out that his hammer could only weigh as much as 200 billion elephants now, instead of 300 billion elephants.

These two points are important to keep in mind, because the ordinary flaw humanizes the character, but we as the viewer/player must also think that the character can be redeemed. For an extreme example, Solid Snake is a tough, no-nonsense super spy who can kill you with his bare hands (something unrelatable to many of us), but he has some trust and intimacy issues (which, even if we can’t personally relate, we can empathize). But – and this is critical – we can understand why Snake has his issues, and we can forgive him for keeping people at an arm’s length.

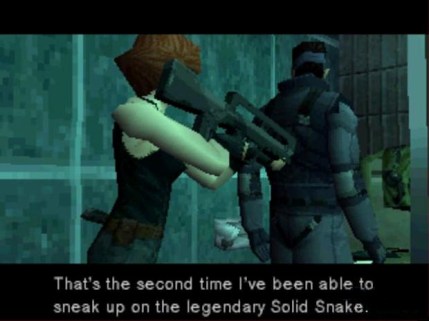

On a smaller scale, when we see him fail in little ways, it drives home that he’s still a human who can make mistakes, like in the Metal Gear: Solid example here:

When he makes mistakes, when he doesn’t see the twist at the end coming, and when things don’t work out the way he wanted, he is actually successful in burrowing into our hearts a little more.

The Power of Pathos

Humans are flawed, and so it’s easy to see why we might identify with a character who shows flaws, especially if they are ordinary. But in a virtual world where we can be anything, why would we choose to follow the exploits of a character who makes mistakes, and experiences heartache?

As we’ve discussed elsewhere on this blog, empathy is a feeling that drives us to relate to other people and experience what they are experiencing. Humans are, in fact, emotional beings. So, when we are exposed to a character with an emotional backstory, we get wrapped up in the pathos, because it gives us an emotional “fix,” if you want to think of it in those terms. (For a quick-and-dirty guide to what pathos is, you can find one here)

But this again begs the question of why. Why do we want to experience negative emotions, if we have the option? The answer is surprisingly simple: by being given the opportunity to feel these emotions behind the safety of a screen (or behind the pages of a book), we are given a chance to experience these emotions within a safe context. If a person dies in real life, you can’t pause life to process what just happened, and you can’t distance yourself and look at the grief with a critical eye.

You can do that with a game. You have control over how you experience those emotions. You can pause the game; you can even turn it off and come back to it later without consequence. In real life, there’s no actual “pausing to come back later.” It’s happening, and you can’t just “turn it off” until you’re ready to deal with it.

Games let us explore these scary and “unsafe” emotions from a safe distance, and let us experience and practice what it would be like in those situation, were they to be real.

The Big “So What?”

Relatability is immensely important in creating character depth and for fostering interest in the character, because relating to another person is more powerful than looking up to someone perceived as “perfect.” We want to build connections with other humans and, as we’ve talked about before, we want to see that we – with our flaws – can move beyond what we are and become the person we want to be.

When we find and relate to a character who is like us, we are also free to experience their emotional experiences from a safe distance. We can feel the pang of death, rejection, or failure without actually having lost anything; we can feel rage, anger, and hatred without risk of harming something real; and we can feel the powerful rush of pride when we accomplish something difficult, spurring us (hopefully) to seek that feeling in the physical world.

All Those Who Wander…

One such hero is Wander from Shadow of the Colossus. Although he’s a pretty quiet character, we are immediately drawn in to his story as he tries to save the life of the woman he loves by going on and epic quest to kill the titular colosi. His flaw is that he is in love… When the twist at the end happens, I’m not sure any of us sat there thinking, “Good, you deserved that,” so his flaw – which drove his actions – was forgivable. We were probably rooting for him, and maybe a little depressed when the heroic quest didn’t work out in the end (at least for him). This is a game that is critically acclaimed for not only its art and story, but its characters. There’s only one character, and he doesn’t say much, so the only thing we can relate to are his actions (which aren’t flawed) and his motivations (which are).

What do you think? What beautifully flawed heroes do you like, or do you prefer your heroes to be perfect in every way? Let me know in the comments!

Until next time, thanks for stopping by, and I’ll see you soon!

~Athena

What’s next? You can like and subscribe if you like what you’ve seen!

You can also:

– Support us on Patreon, become a revered Aegis of AmbiGaming, and access extra content!

– Say hello on Facebook, Twitter, and even Google+!

– Check out our Let’s Plays if you’re really adventurous!

Leave a comment