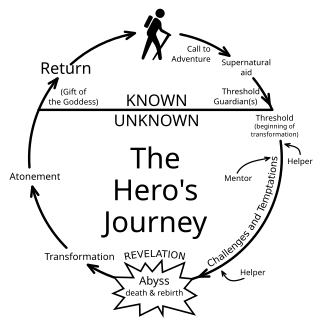

In mythology, there is something called the monomyth, or the “hero’s journey.” It is a set pattern of events that a story/character will progress through during the story. This journey usually entails the hero going on an adventure, triumphing in some way, and returning home a transformed in some way. A long time ago, I posed a little thought experiment about how Loghain from Dragon Age: Origins, actually progresses through the hero’s journey, despite being the main antagonist of the game.

More recently, I was talking to my friend Imtiaz over at Power Bomb Attack about Journey, an indie game developed by thatgamecompany and published by Sony for the Playstation 3. We agreed that it can provide a powerful and moving experience for gamers, and, upon some reflection, I realized that this profundity comes from the game setting the player on the hero’s path and letting the player personally experience, for him or herself, the great monomyth.

What is the Monomyth?

The study of hero’s tales and mythology has dated back to the late 1800s, but John Campbell is the one most often associated with the idea of the monomyth. Basically, what Campbell poses is that all heroes across all heroic tales follow the same progression from beginning their story in the mundane everyday, traveling through a series of fantastical journeys and obstacles, and then finally returning to their original world, transformed and wiser for their journey. This can be applied to the stories of Bilbo and Frodo Baggins in The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings trilogy, to the story of the Buddha, Jesus of Nazareth, and even Harry Potter*.

Humans love stories; it’s how we learn and connect with other people, both of our time and from the people who have come before us. What the idea of the monomyth proposes is that all great stories found in the human tradition of storytelling follow a pattern that resonates with us. This is both the reason so many story follow the monomythic progression, and why stories that echo of it resound with us so strongly.

So, without further ado, let’s see how thatgamecompany’s Journey lets the player follow in the footsteps of the great hero’s journey.

1. Call to Adventure

The moment in the story when a life-altering, sometimes supernatural event, occurs. It is the catalyst for the hero to begin his/her journey.

In Journey, the game opens up with no explanation, no directions, and no call to action. It simply shows you the landscape and, towering above the sand in the distance, a giant, shining mountain. Here, the call to adventure is the thing that drives all humans forward: curiosity. What is the mountain? Where are we? What are those small monuments for?

In this case, the supernatural event is putting a person into a strange environment with no explanation and no clear expectations. For a video game, this is a subtle yet extraordinary way to pull the player in and (politely) force them to put themselves into the game. The avatar doesn’t have any reason for progressing through the game, but the player does. Thus, Journey sets the player on the hero’s journey.

2. Refusal of Call

Oftentimes, the hero/heroine does not believe that the call is important and will not heed it (like Simba from The Lion King). The hero can exist in this state, but in those cases is destined for a fall (King Minos*). The call can also be impeded by another person, like in the Harry Potter series*.

As the game progresses, it might seem like there is no point at which the avatar/character/player refuses the call to adventure. Simply by continuing on and exploring, we as players are answering that call. However, the game cleverly works the refusal into its very mechanics. When the player becomes too adventurous and deviates too far away from the path, the game pushes the player back via a gust of wind.

So, in addition to our natural curiosity, there is a path for us to follow. There is a purpose for our travels. And any time we try – inadvertently or purposefully – to leave the path, we are refusing the call to continue on our journey.

3. Supernatural Aid

A conveniently-placed character will offer aid to the hero along his/her journey.

One element in the game provides us – via our avatar – with aid, and they are placed conveniently throughout the game areas: the scarf pieces and the cloth creatures. By lengthening the scarf of our avatar, we are able to reach new heights in the game, overcome new obstacles, solve harder puzzles, and bypass difficult terrain more easily. Likewise, the cloth creatures can replenish our scarf’s power, as well as give us short rides over other obstacles or across distances that we could not manage under our own power.

4. Crossing the First Threshold

The hero reaches, and crosses, what Campbell calls the threshold of a “zone of magnificent power.” This is the moment the hero becomes to be immersed in the event/happening that is larger than him/herself.

This happens fairly early int he game. When the Traveler (the name of your avatar) finds the first ruined structures in the desert, and goes to explore, the first hints that there is more to the world than sand is revealed. Trapped within the metal cages is one long scarf piece, which the Traveler can free.

The structure the scarves are trapped within is the first hint that there is something much larger than us in the world. After all, the metal body is long and segmented, looking like the half-buried skeleton of a large creature. And it traps scarves that look a great deal like the scarf our avatar wears…

5. Belly of the Whale

Following a crossing of the threshold, the hero finds that he/she does not conquer the power of the threshold, but falls into the unknown.

The first time in the game the Traveler is truly in danger is during the underground level. The beasts that we have only seen as husks on the ground are alive and well, patrolling the skies and searching, it seems, for the unwary Traveler (pun unfortunately intended). It doesn’t matter how long your scarf is, or how much exploring you have done above-ground, because here the Traveler can only sneak and, eventually, is forced to experience the sheer power of the mechanical watcher/war machine as they – at the least – chase the Traveler to the end of the cavern and – at the worst – attack the Traveler and rip the our scarf to pieces.

In this cavern the Traveler is helpless and completely at the mercy of the machines. We can only move slowly, keep to the shadows, and hope for the best. In fact, there is a trophy for completing the “level” without being seen, since that by itself can be quite a feat.

6. Road of Trials

These are a series of trial that the hero must overcome, perhaps using a magical instrument like an amulet, or other supernatural forces. Often, the hero will fail the trials before being successful.

This is one of the easiest stages to parallel in the game. Throughout Journey, we are asked to solve puzzles, which, like a hero’s Road of Trials, must be completed before we are able to progress. Additionally, because we are interacting with the game through our avatar, we are the ones who fail when we don’t utilize our knowledge or skills the best way. Sometimes, we must use our supernatural force – our magical scarf – to complete the puzzles and progress.

7. Meeting with the Goddess/Woman as Temptress

In both of these situations, the hero is asked to either sacrifice a long-held belief after meeting an important, often-female character, such as a goddess, oracle, or other important woman (like Princess Leia from Star Wars), or must resist giving in to temptation, either physically or mentally, in order to grow in strength as a character.

It’s easy to dismiss this step in Journey, since this one is one that doesn’t always need to be present for the monomyth to be complete. However, although I’m not sure if the Travelers have genders, at certain points throughout the game we meet a figure robed in white, who gifts the player – via the Traveler – knowledge of the past. This knowledge blurs the line a bit for the player/traveler relationship. It is new information to both, and it sometimes hints at upcoming trials, like the appearance of mechanical war machines that hunt Travelers.

8. Atonement with the Father

This often represents overcoming that which has come before, or an abandonment of thinking limited by the id or ego*.

This is another step that doesn’t always need to be present in a story, but it’s possible that, as a player, our realization that the Traveler is somehow connected to the beings who destroyed their world could represent overcoming pre-conceived ideas about the game, the story, or the Traveler itself.

9. Apotheosis (The Climax)

This is the moment when greater understanding is achieved, enabling the hero to complete the final and most difficult part of their task.

The final area, the snowy mountain, is this last step before the “endgame” of Journey. There is no way for the Traveler to complete this level either alone or with a companion, and the entire area is a battle against the temperature, the elements, and the mechanical war machines.

However, upon the ultimate “failure,” the player/Traveler is surrounded by the figures in white, offering help in those final moments. I believe that this is very symbolic of gaining “understanding” through a spiritual experience of some sort, propelling us into…

10. The Ultimate Boon

The achievement of the quest.

We make it to the mountain! And we are duly rewarded with a beautiful area to explore, without fear of our supernatural power (flying abilities) running out or of coming to any harm. I love the imagery used here, as the devs seemed to go out of their way to make the area as aesthetically pleasing and inviting as possible.

11. Refusal of Return and Magic Flight

Refusal of Return is when the hero does not want to leave the enlightenment and joy of the discovered world. The Magic Flight refers to an instance of having to “escape” with the ultimate boon in order to return to the ordinary world with the new knowledge*.

I combined these two because of how they are presented in-game. The refusal of return is another instance of how the player simply enjoying the game world is fulfilling a step of the hero’s journey. After the trials of the game, and the final push up the mountain, the player is given the freedom to fly and float joyfully above the clouds without any hindrance, either from war machines or from the power of the scarf running out. While the player can simply pass through the area to reach the end, I would pose that many of us took a little extra time to explore this beautiful and peaceful world.

The magic flight doesn’t occur as per its definition, since the Traveler doesn’t need to “escape” from an antagonist with anything, but there is no denying that the player finishes the journey with knowledge and experiences that they hadn’t had before, and can re-start the game with this new knowledge.

13. Rescue from Without

Occasionally, the hero needs help from an outside source during the return journey. This could be in the form of advice, shelter, or a literal rescue, like the eagles appearing in The Lord of the Rings: Return of the King.

This step doesn’t really occur in the single-player experience of Journey, as there is no opposition to us finishing the game and returning “home.”

However, in the online multiplayer – a beautiful experience where two strangers meet in the game but cannot communicate outside of the musical chirps that the characters can make – strangers/other Travelers may appear where you are, all on their own journeys. These other Travelers may be more experienced players (and the most experienced ones will have white robes compared to the usual red), and – if they see another player struggling – may provide a silent guide.

Or they might provide unexpected yet company on an otherwise solitary (and sometimes lonely) journey.

This is not technically a “rescue,” but fits in this category due to the social or emotional “shelter” that finding an unexpected companion may provide.

14. Crossing the Return Threshold

Not only reaching “home,” but also retaining the knowledge of the extraordinary world and knowledge discovered.

As the Traveler lightly lands back at the beginning of the game, the player again experiences this step of the hero’s journey. We have literally arrived back where we started, but know we are a little wiser about the game world, the journey, and the joy that awaits us at the mountain.

15. Master of Two World

The hero is able to transcend the two worlds, integrating the knowledge of each.

While not the most important step here, this is again one that the player experiences through the avatar. The player can now guide the avatar through the worlds again, finding the secrets more easily and completing the journey with (hopefully) less trouble than before.

16. Freedom to Live

Neither anticipating the future or regretting the past, the hero lives entirely in the moment.

Another step that the player is craftily asked to experience: when we sit back to think about the game we just played, we begin to have an inkling that maybe it’s not about where we’re going, or where we’ve been, but where we are. Perhaps, all along, this has been about the journey, not the destination.

What do you think? Is it Journey‘s adherence to the monomyth – and how it lets the player personally experience the hero’s journey – that makes it such a powerful experience? Have you played Journey? What was your experience like? Let me know in the comments!

Thanks for stopping by, and I’ll see you soon!

~ Athena

**This article has some extra content available over at Patreon, if you are so inclined!**

What’s next? You can like and subscribe if you like what you’ve seen!

You can also:

– Support us on Patreon, become a revered Aegis of AmbiGaming, and access extra content!

– Say hello on Facebook, Twitter, and even Google+!

– Check out our Let’s Plays if you’re really adventurous!

Leave a reply to The Shameful Narcissist Cancel reply