Horror is a genre that, when done well, gives us stories that can linger and haunt us even after we’ve closed the book or turned off the television. It makes us look at the world with new eyes, even if for a short period of time. Sometimes, it’s easy to try and classify horror as just needing a good monster, or a frightening atmosphere, or some great jump scares, but the most horrifying types of horror are much more complex than that.

While many considerations go into crafting a good horror experience, like whether the monster will defeat the protagonist or be defeated, or whether it will employ Lovecraftian or existential elements, we’ll be focusing on the most bare-boned reasons as to what makes a horror story linger and truly frighten us after the game is turned off.

Building Horror

One of the most important things a game or story can do when presenting a horror scenario is use something called the tension/release cycle. This conveniently-named tool requires a slow build of anticipation within the story, adding tension and, in laymen’s terms, stressing the player out. As this happens (if it’s done well), the player him/herself will begin to feed the tension, both wanting the break in tension/release and dreading what will happen to cause the release, thus adding more tension.

Again, assuming this is done well, this build up continues until you almost can’t take it anymore, and you feel like something just needs to happen, when

A loud noise blares, another character appears, the monster pops out, or a harmless cat jumps onto the windowsill (oh thank goodness, Pepper, it was just you…).

And then the cycle repeats.

But the thing about this is that after the release, we feel better. We actually feel less scared – after the initial startle passes – than the moment right before the release. This is how we can engage with horror media for hours at a time and not suffer any long-term stress effects: by utilizing the tension/release cycle, horror stories not only keep us right where they want us, but also offer small psychological releases so we don’t, you know, accidentally experience a brief psychotic break. No, seriously.

A game like Slender or even Gone Home do this well. As the player traverses the gamescape, we are acutely aware of the environment (because we are on alert for Slender Man or because of the uncanny, which we’ll talk about below), and are subconsciously counting the moments when… nothing happens. We know something is coming. We know it’s going to be scary, and yet we don’t know when it’s going to happen. While Slender Man is horrifying, it’s almost a relief when he shows up, because we can finally be properly scared, maybe scream, and run away (either in or out of game, whatever does it for you); we are able to get all of that nervous energy out. And what a relief when the monster finally shows up!

But where does this slow anticipation come from?

Uncovering Uncanny

A long, long time ago, I briefly dropped the term “uncanny valley” in a post about art, graphics, and games. InsertMemoryCard was the only person who commented on it, and while I had originally wanted to wax poetic about the uncanny valley in its own post, I was never happy with how it looked. But now we’re talking about horror, so the uncanny fits right in! But before we talk about the uncanny that is found in games, we need to establish what the “uncanny valley” is.

As humans, we are experts at determining what is human and what isn’t human. We know, without a doubt, what humans are and what they look like.

These are humans.

These are not humans.

I’m being serious. We do this without consciously thinking about it, without having to make calculations, without having to stop and reconsider.

We’re even really good at determining whether or not a humanoid-like thing is a human or not.

These are also not humans, even though they sort of look like they’re related in some way to humans.

Interestingly, we’re also good at picking out human-like features in things that are distinctly not human, and happily perceive them as more human-like.

Aw, look at him and his little, expressive eyes! He thinks he’s a people!

In all of the above pictures, we are able to clearly distinguish what is human, and what is not, and that is comforting. We like categorizing things, especially regarding whether things are similar to us as a species, and we’re okay when things are clearly “human” or clearly “not human.” Additionally, the human characteristics in non-human Wall-E are discernible, but because the rest of him is so obviously “not human” (and classified as such), we’re okay with the human-like characteristics.

The problems begin when the human-like characteristics are on an object that looks human, but something is off about it.

Because we are so good at figuring out what is and isn’t human, we are quickly able to pick out the human characteristics, but on the heels of that is our brain realizing that there is something wrong about it. It’s because we’re so good at knowing what humans look like that the photo above bothers us.

We might not be able to put our finger on it, but something is wrong. It looks human, but it is, at the same time, not human. This also begins to explain the revulsion we feel at seeing dead bodies – they look human, but something is missing. Of course, from an evolutionary standpoint, being wary of the dead thing that looks human but isn’t alive anymore was advantageous for obvious hygienic reasons.

Thus, to warn us of potential danger of “not human,” our brains make us feel uneasy.

The “valley” that I’ve been talking about refers to the below graph, which shows how, as things look more human, the more we tend to like it… to a point. When things hit the “uncanny valley,” we are in the same situation as above: the “person” doesn’t exactly look right. On the other end of the valley is, of course, actual humans. Take a look:

So our friend up there tripped and fell into the valley, along with The Polar Express movie and other unfortunate characters from games like L.A. Noir and Medal of Honor.

Unsettling Environments

But what does this have to do with horror? Sure, these pictures are creepy, but easily dismissed as bad animations.

Well, we’re not only good at discerning what is human and what is not human, but also at knowing the way things are “supposed” to look, and finding little things that aren’t the way they’re supposed to be. A flickering light in a house concerns us, because we know that lights aren’t supposed to flicker. Then, we make a logical leap and say that if a light is flickering, then it isn’t in good repair, perhaps because no one lives there. But if no one lives there, then why are the lights on to begin with? And if someone does live there, why haven’t they replaced the bulb?

So, when it comes to the uncanny, our own minds can be more frightening than anything else we’ll come across. At that point, we begin looking for more things that are out of place, heightening our alertness. If we do find something else out of place, then we become more concerned. And thus the tension/release cycle continues.

A good example of this is Gone Home, because while there is nothing objectively scary about the game, it sets the player on edge because so much just seems out of place, both physically and psychologically, in the home you are exploring. The story doesn’t have to work hard to creep the player out – the player’s own imagination builds the tension for it, and so the game only needs to worry about when it will provide the release.

Getting into the player’s head, however, is the surest way to create a horror experience that lingers, and one that will not be easily dismissed once the game is turned off. And if you can get a monster into the player’s head, well…*

Unsettling People

It’s comforting, isn’t it, to be able to think,” Whew, thank goodness things aren’t really like that“? Well, in the most effectively haunting tales, that last net of safety is taken away. These stories hold up a mirror and simply reflect back a horror that could be, that is not too far from our own realities, and/or shows us the depths to which a person can fall.

For this to work, the main character needs to be relatable. While some stories play up the power fantasy end of things, those tend to not be the games or stories that linger or have the most impact. We can understand how scared the Everyman protagonist might feel when thrown into situations out of their control, and some of the most powerful examples of using this is in comparing the movies Alien and Predator. Which is scarier? I’m willing to bet you answered Alien with poor, doomed, working-class Ripley, and not Predator with its badass Major Schaeffer who is anything but helpless.

But why is this? The best, most lingering types of horror are about disempowerment; they make us feel frightened even in a safe place. Unlike the jumpscares or the gross monsters of action-horror games, we can’t chuckle off how unsettling these games are. The complex relationship between the monster and the protagonist needs to be tipped in the monster’s favor in order for us to feel that hopeless horror that sticks with us.

One way to do this is to have the protagonist fail, usually right after looking like they would succeed. It leaves the audience unsettled, especially if they found themselves identifying with the character. In fact, it can at times call into question our very idea of self efficacy and free will; after all, if the character thought they had won, and had done everything right, or worse, simply were in the wrong place at the wrong time, and yet still failed, what could that mean for us?

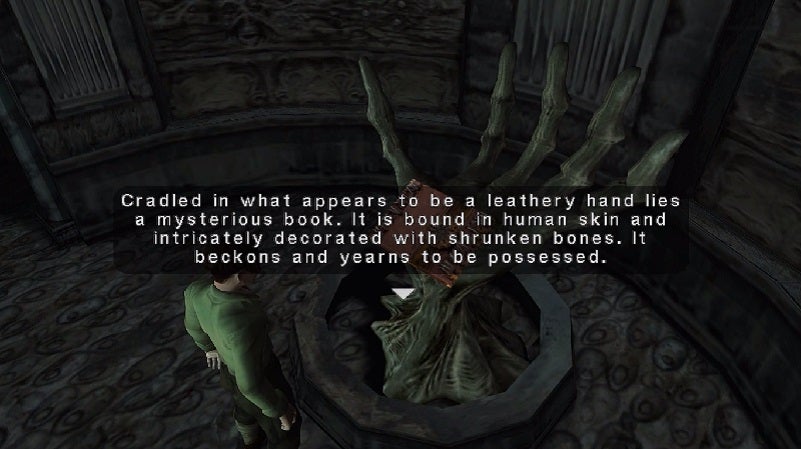

Games like Eternal Darkness fall into this category, pitting us against a growing horror that slowly and meticulously defeats the protagonist one moment at a time. The game literally shows how the horror chips away at Ashley’s sanity, just as it would for any of us (let’s be real here).

My favorite type of character, however, is when a story simply reflects back the darkness that hides just beneath the surface in all of us. One that shows us what could happen if we let out some of our more base desires that are only held back by a veneer of socialization. You know, those horrible little ideas that pop into your head for a moment because you think, “How terrible,” and dismiss it.

Horror protagonists take those ideas, or those feelings, and pull them into reality. Showing the depths to which humans can fall challenges our expectations that “hero” of a tale is heroic. In this cases, the hero falls to some other force, sometimes very unknowingly, and instead of being the unwavering hero we want them to be, wind up being the villain in their own story.

As the hero in our own stories, though, what does that say about what could happen to us?

Too Long; Didn’t Read

At the end of the day, there are many different kinds of horror, many different ways to present monsters, and many different ways for horror protagonists to be portrayed. But to make the horror linger, to rattle the audience, and to blur the line between what happens behind the screen and what happens in front of it, showing the potential depth to which the gamer could easily fall by presenting them with a relatable, realistic character who is, themselves, the monster in their own story is more effective than any other means of horror-building.

What do you think? Do you prefer your horror unsettling and uncanny, or empowering and easily dismissed? What’s your favorite horror game? Did it have any of the elements listed above? Let me know in the comments!

Thanks for stopping by, and I’ll see you soon!

~ Athena

**Extra content available on this topic on Patreon!**

What’s next? You can like, subscribe, and support if you like what you’ve seen!

– Support us on Patreon, become a revered Aegis of AmbiGaming, and access extra content!

– Say hello on Facebook, Twitter, and even Google+!

– Check out our Let’s Plays if you’re really adventurous!

Leave a reply to Mr. Panda Cancel reply